Do You Want to Hear a Story?

Posted by Robert Hendrick on May 9th 2019

It’s a family friendly dinner table sort of story for home. A classic tale you to be told at work over your desk or sitting at a conference room table.

It’s a telling of history preserved and of nature reminding builders of its superiority.

It’s a story over 100 years old, but still as fresh and relevant today as it was then.

Curve worn and sporting a vertical split head defect starting to manifest itself, the service life of this section of rail harkens back to the height of the Industrial Age. That little occlusion visible in the top right of the rail head preserves and stands as proof of one of the most enduring stories of that era.

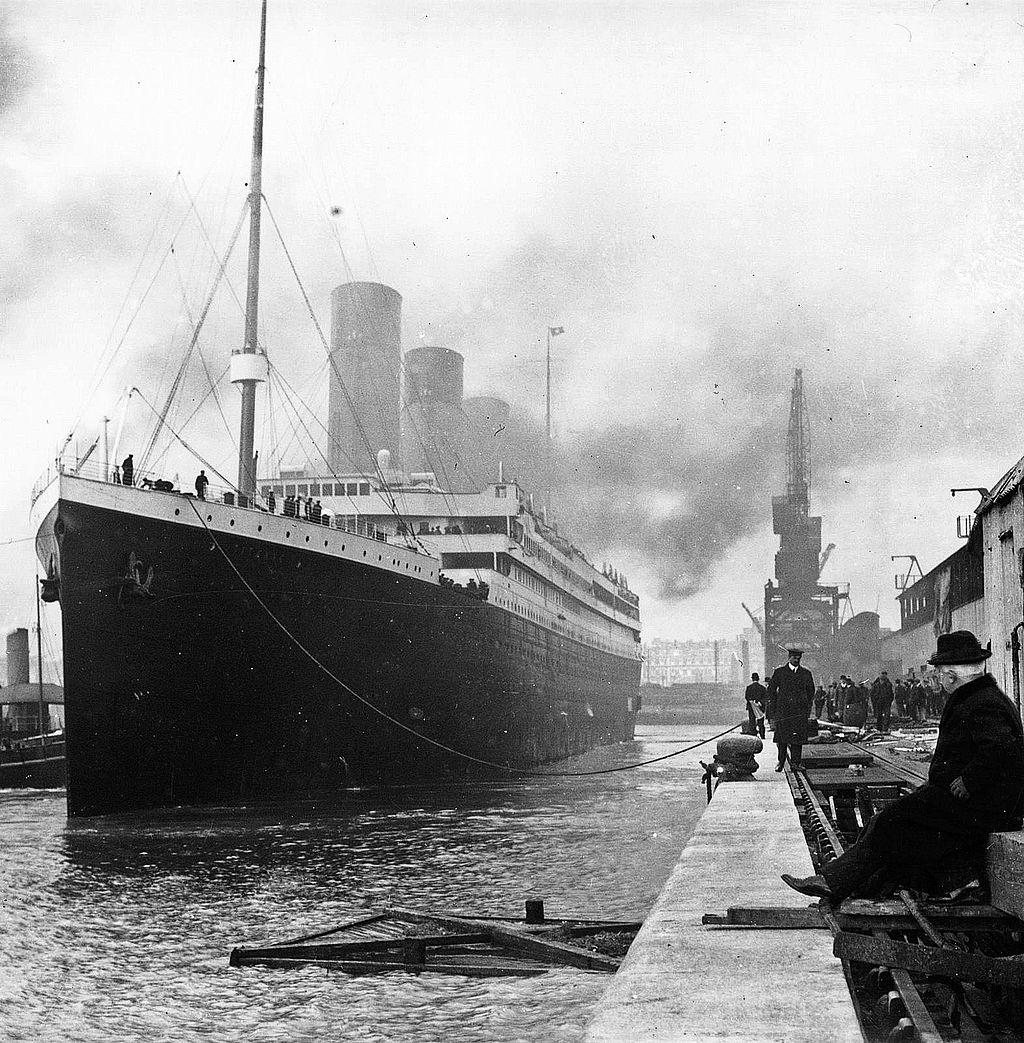

The year was 1912, and entrepreneur Andrew Carnegie had outlived Cornelius Vanderbilt and George Pullman, other legends of the railroad industry. Carnegie was building a reputation as a philanthropist on the heels of the sale of his steel foundries to J.P. Morgan who was in the midst of creating his own empire. The railroad had already redefined luxury travel, and the Titanic was setting sail from London bound for New York.

That small occlusion – the little fissure in the head of the rail - is a strand of glass - to put it in layman's terms.

Made with the long since outdated Bessemer steel making process, that relatively minor flaw results from uneven and/or incomplete heating to burn off impurities like silica and other minerals that naturally exist in iron ore. While Bessemer process was quite good in the late 1800s until the very early 1900s, the method often did not get the iron ore hot enough to "burn off" the silica.

As a result, when a steel billet was heated and rolled into a rail, pockets of silica turned into long strands of what is essentially glass. While the other portions of the rail were quite strong and compensated well for these imperfections, these fine slivers of glass were a hidden accident waiting to happen.

Larger fissures would lead rail to fail resulting in derailments and other failures.

Bessemer process steel was the best available at that point in the Industrial Age. It went into every means of transportation on land or sea.

The unsinkable Titanic shook the very foundation of the late Industrial Age when it went down. Mankind’s triumph over nature didn’t survive its maiden voyage.

Blame has been placed on nature and the iceberg, on poor seamanship and even books have placed time travelers there to put blame on the extraordinary. Some want to blame it on a fire.

However, samples from the hull of the ill-fated passenger ship offer a bit deeper insight. Built with Bessemer process steel – there was none better at the time – the ship's hull was filled with small occlusions like that seen this rail.

Once the sharp edge of the iceberg pierced the hull of the Titanic, it should have stopped, but it did not. The berg tore through moving from one occlusion to the next in the steel and from one compartment to the next compromising the integrity of the ship. The cold made the steel more brittle and the icy knife-edge of the submerged iceberg steadily shredded not only the ship, but the arrogance of the Industrial Age.

Make no mistake; this steel is tough. It has a high carbon content that makes it hard – extremely hard. It served for over 100 years before being removed from service handling loads that far exceed its original expectations. But its stint as part of the railroad is over.

Now we step in to preserve the history.

These well-worn and heavily weathered sections of steel won’t run 250,000 railcars any longer or endure the grind of heavy diesel locomotives.

These pieces of rail will become classic tables, each with their own story defining their place in history.

This will become a gorgeous dining room table or an executive style desk.

And just like the Titanic, if you put it in water, it will sink.